Hermes International S.A.

A look at controlled scarcity, vertical integration, and sales to China.

Hermes International S.A. (“Hermes”) is a leading producer of luxury goods founded in 1837. I have been a long-time fan and customer of its products, and I have long admired how Hermes manages its business and protects its brand. I was once a shareholder and consider selling it one of my greatest investment errors. Perhaps I’ll get another chance to buy it. In the meantime, I would like to discuss just a few attributes of the business that I find interesting. The first attribute is its willingness to sell certain items well below the market clearing price and the results of this decision. Second, why Hermes’ decision to be vertically integrated is important to the business. Finally, we will see how its expansion into Asia impacts other parts of the business.

Artificially Keeping Prices Low in a Supply Constrained Item:

While Hermes is known for various items (such as their whimsical silk neckties and women’s scarves), two of their handbags, the Birkin and Kelly (named after actresses Jane Birkin and Grace Kelly), have reached iconic status levels. The Wall Street Journal estimates that Hermes limits production of these bags to about 120,000 units per year and that the two bags alone generate 25% to 30% of Hermes’ total revenue – note its revenue in 2022 was €11.6B. Furthermore, Hermes sells these bags below the market clearing price. If you are lucky enough to be sold one at a retail location, you can walk out the door and immediately sell it for material gain. It seems like Hermes is leaving money on the table by not raising the price of these bags.

Hermes may be leaving some Euros on the table, but I would view it not as lost revenue, but as an investment in the brand. The supply/demand mismatch creates scarcity in these two bags and that scarcity likely creates more demand for these bags (Veblen goods), elevates the overall status of Hermes, and creates demand for Hermes’ other products as customers buy Hermes other goods to build a relationship with the company in hopes of being allocated a bag at the below-market retail price. The last five or so years excluded (the demand for many luxury goods has taken off, we will cover this a bit later), I have seen this scenario on only a handful of other occasions. For several decades Rolex employed the same strategy with the pricing of their Stainless Steel Daytonas. The highly desired watches were reserved for a retailer’s best customers and traded at a premium in the grey market. Ferrari has employed the same strategy with some of their limited-edition cars. The price appreciation of several limited-edition Ferraris has exceeded that of the S&P 500. To be allocated one, you have to buy several of their other cars and work your way up to a highly coveted limited edition. If you get the phone call, you are often given a price range, and may not even be given the type of car the limited edition will be. You say yes, despite not knowing, because if you turn it down, you may not get another chance to buy a limited edition. Limited editions often sell out before the buyer even knows what they are paying or what they are getting.

With a quarter to a third of revenue coming from leather goods, which is driven by these two bags, the revenue of the company is likely much stickier than one would expect given its discretionary nature. If you are wealthy and you “get the call”, you likely are going to buy, as you may never get another chance.

Vertical Integration:

Hermes is fanatical about its product quality. Around half of its employees are production employees. A third of its employees are leather workers. Hermes often owns its raw material suppliers completely, as is the case with an alligator leather tannery in the US, or via a large equity stake, as is the case for the Swiss manufacturer of Hermes watches. It is easy to see the benefits vertical integration has on maintaining product quality, but there are a couple of other benefits worth considering.

The next benefit is that vertical integration from production of raw materials to the retailing of finished products likely helps mitigate the production of excess inventory, which would result in discounting of finished products. Discounting is antithetical to maintaining luxury status, and for what it is worth, I have never seen Hermes discount anything.

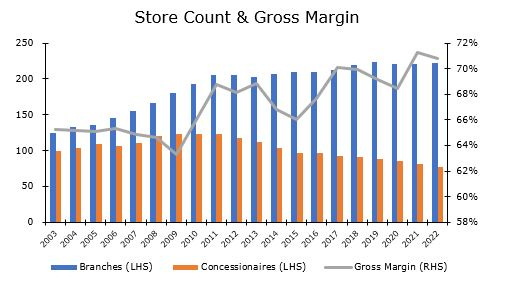

As far back as I have found information on the subject (2003), Hermes has continued to reduce the number of Concessionaires (non-company owned retailers of their products) and increase the number of company-owned retail locations. In 2003, only 56% of their retail locations were company owned. In 2022, that number increased to 74%. Controlling the retailing of their products likely contributes to the no-excess supply benefit mentioned above. Another huge benefit of this transition is that Hermes was able to replace wholesale revenue with retail revenue. While we don’t know the ultimate answer without more information, I would argue that the increase in margins between 2003 and 2022 likely came from the conversion of wholesale revenue into retail revenue.

A quick aside, all three of the companies mentioned in the article, Hermes, Ferrari, and Rolex, each are on the higher end of the vertical integration scale.

Asian Expansion:

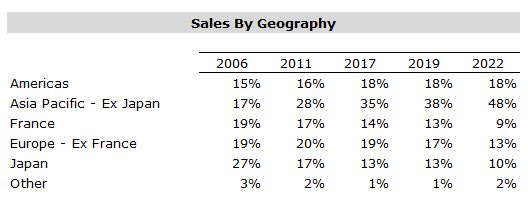

The below chart shows sales by geography for some selected years. There are a couple of items that jump out to me, which lead to some questions and thoughts. First, France sales, which are highly dependent on tourism, are not back to its pre-COVID percentage levels. Will Hermes see a benefit as travel normalizes?

The second item that jumps out is the Asia Pacific – ex Japan – expansion. In 2006, Hermes generated only 17% of its revenue in the region, compared to a whopping 48% in 2022. What are the implications of this to Hermes and other luxury goods producers? First, I would argue that the exposure to the region likely increased the risk to the revenue stream. Every now and then, the Chinese government cracks down on corruption. These crack downs usually have a large impact on the sales of luxury goods, as corrupt officials are given luxury goods as gifts or buy them with ill-gotten money. That seems obvious, and the risk is well understood by investors in luxury goods producers.

Another implication of increased sales to the Asia Pacific region is likely the exacerbation of the supply/demand mismatch in the Kelly and Birkin bags and the likely spread of this situation to other, perhaps lesser, luxury goods products. Assuming Birkin limits production of the Birkin and Kelly bags to 120,000 units per year, opening an entirely new market just makes the supply/demand mismatch even worse. Let’s take a look at a similar dynamic in Rolex. Historically, the only watches from Rolex that consistently enjoyed a premium in the grey market were the Stainless Steel Daytonas. Sometime in the middle twenty tens, that privilege was extended to all Rolex Stainless Steel Sport Watches, and ultimately to several of their precious metal sports watches. Given this dynamic, it is easy to see how some of the cachet of some ultra-premium brands or items has spread to some lesser brands or items. Also, it is hard to see what will break this trend. Rolex produces about a million watches per year, with plans to go to 1.25 million over the next five years. Will a CAGR in supply of 4.6% be enough to tame the demands of the global middle and upper classes?

Disclaimer: For entertainment purposes only. Not an offer to buy or sell a security. Do your own due diligence.

Nice write up - was mentioned on the latest Acquired podcast

Nice piece! Thanks for putting it together.