Using the word era to describe a time in the life of a company does not seem appropriate. Companies go in and out of business all the time. The average lifespan of a company in the S&P 500 is just over 21 years. But, in the case of Texas Pacific Land Corp. (“TPL”), the word fits. TPL first went public in 1888. Despite its long history, I can think of only a handful of monumental changes that rise to the prominence of the use of the word era. There is the change from TPL’s structure being a trust to a c-corp. (trust era vs. c-corp. era). There is the pre- and post-fracking era. There is the return of capital vs. high-cash, acquisition era. The c-corp. and fracking transitions both benefited shareholders. The transition from the return of capital to high-cash acquisitions era is not off to a good start and is concerning. It is this transition I would like to explore.

I can easily find financial information on TPL going back to 1993. Also, the fracking era didn’t begin into the 2010s. Let’s look at what was going on from 1993 through 2009. The cumulative cash from operations generated those years was ~$112mm. Over the same period, less than $1mm in investment capital was required. This left an ample amount of free cash flow, most of which was returned to shareholders (more correctly, unit holders), with about 70% being returned via share repurchases and the balance being returned via dividends.

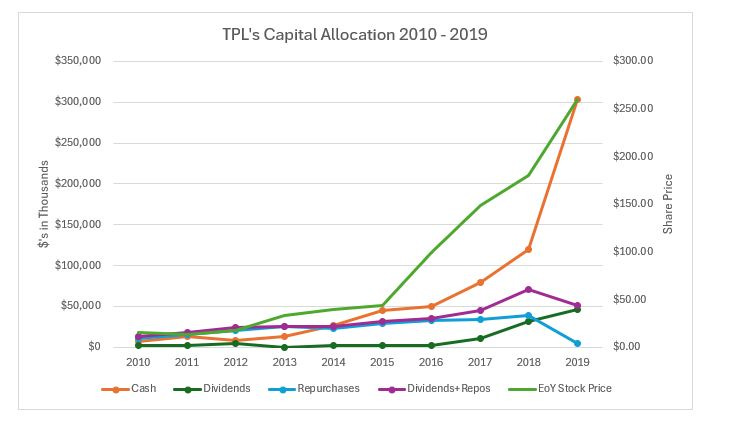

As the fracking era arrived, the amount of cash TPL generated grew exponentially. At first, the practice of returning most of the excess capital, while privileging share repurchases, continued. A shift occurred in the latter 2010s, around the time long-time trustee Maurice Meyer III became ill and then subsequently retired. The chart below showed that the balance sheet cash balance slowly trended up until shooting up in the later years. Also, share repurchases were much greater than dividends until 2018, when dividends almost equaled share repurchases before overwhelming them in 2019.

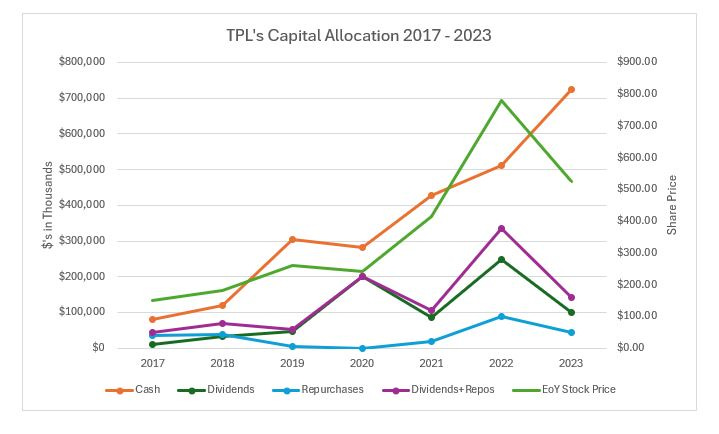

Unfortunately, 2019 was not a one-year phenomenon. Share repurchases were all but cutoff from 2019 to 2021 (including none in 2020, an almost unforgivable offense to shareholders), before returning in 2022 and 2023. Despite the return in those years, they were overwhelmed by dividends, which represented nearly three-quarters of capital returned to shareholders in 2022 and 2023. Meanwhile, the amount of cash on the balance sheet ballooned to $725mm by the end of 2023, and $895mm just six months later.

What Caused TPL to Shun its Practice of Returning Capital to Shareholders?

Between 2010 and 2020, TPL’s revenue grew 24.4x while its cash flow from operations grew 29.3x. Over the same period, its share price grew only 17.4x. While TPL briefly traded at an all-time high in 2019, given the share price’s under performance relative to revenue and cash flow growth, valuation was not likely the cause of management building such a large pile of cash. At some point, management became enamored with deploying capital via acquisitions, a folly of many a management team (particularly when a team has limited experience deploying capital in such a manner). Perhpas they spent too much time with snake charming investment bankers. Evidence of this came out during the trial between TPL and its shareholder/board members, Horizon Kinetics and Softvest. In 2021, TPL initiated a process to acquire assets from Occidental Petroleum in a deal that would have likely resulted in a transaction greater than $1.5bn in size. In 2022, TPL submitted a non-binding proposal to acquire Bringham Minerals, Inc. in a $1.9bn transaction valuation. Neither of the transactions were consummated. That said, they did seem to provide sufficient distraction to inhibit material share repurchases; TPL ended 2022 with $511mm in cash, while buying back only $88mm in shares.

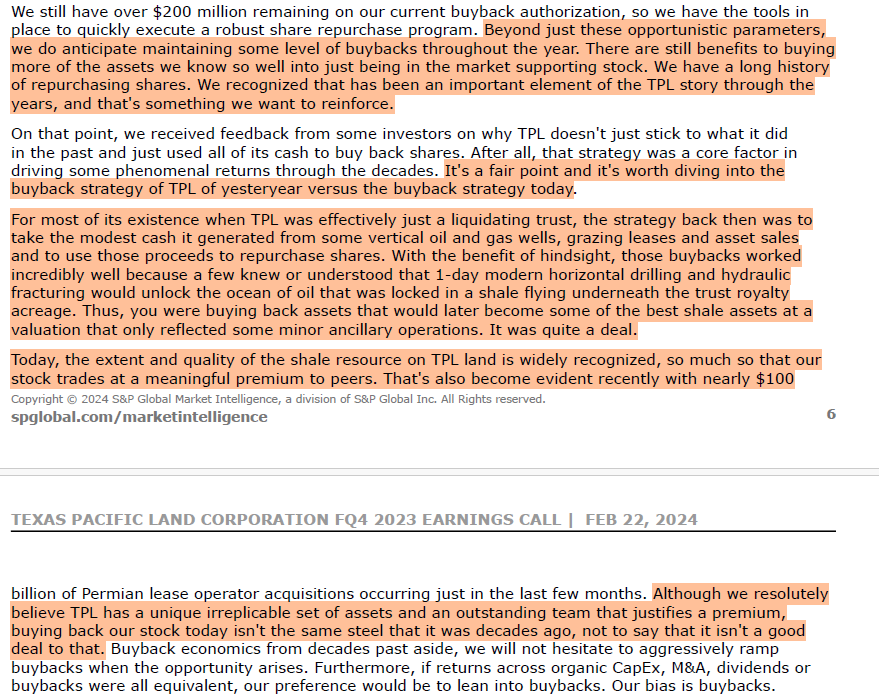

On the fourth quarter earnings call on February 22, 2024, management gave probably their most comprehensive thoughts on share repurchases. The excerpts are below, but here is the summary:

They understand that buying back stock is buying a claim on existing assets.

They got off to a good start in their comments!

They look for double digit IRRs at an oil price of $75 and gas price of $3.

I find it interesting that they did not mention assumptions that determine the value of the land and water businesses.

They noted that they received feedback from investors questioning why not stick to the buyback practices of the past. Their response is telling.

“For most of its existence when TPL was effectively just a liquidating trust, the strategy back then was to take the modest cash it generated from some vertical oil and gas wells, grazing leases and asset sales and to use those proceeds to repurchase shares. With the benefit of hindsight, those buybacks worked incredibly well because a few knew or understood that 1-day modern horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing would unlock the ocean of oil that was locked in shale flying [sic] underneath the trust royalty acreage. Thus, you were buying back assets that would later become some of the best shale assets at a valuation that only reflected some minor ancillary operations. It was quite a deal. Today, the extent and quality of the shale resource on TPL land is widely recognized, so much so that our stock trades at a meaningful premium to peers. That’s also become evident with the nearly $100bn of Permian lease operator acquisitions occurring just in the last few months. Although we resolutely believe TPL has a unique irreplicable set of assets and an outstanding team that justifies a premium, buying back our stock today isn’t the same steel [sic] that it was decades ago, not to say that it isn’t a good deal to that.” The expand on M&A. “We approach M&A similar to buybacks……Again, the goal here is to generate at least double-digit IRRs in invested capital and incremental cash flow per share.”

There is a lot to unpack here, let’s start with recognizing that a main creator of value is the royalty acreage having exposure to what would become hydraulic fracturing in the Permian Basin.

This raises the question; how much value would any management team add? The CEO certainly wanted to take credit for some of the premium in the price by noting the “outstanding team”, but it is a fair question to ask if more value would have been created if they had stuck to the past share repurchase strategy.

Management mentions that the value in TPL’s shale resources are widely recognized (stock price movement post this call would say otherwise, but we will get back to this). If that is true, wouldn’t the value of the assets they want to buy also be recognized?

They mention that TPL trades at a premium to its peers, but they leave out their valuation methodology for non-royalty assets, which raises the question on how good are their comps?

Management continued that TPL isn’t the same steel [sic] that it was decades ago. First, I don’t think I have ever heard a CEO blatantly talk down the value of his stock. Second, it’s worth noting that the stock more than doubled within 8 months of this comment.

Management mentions that they are looking for at least double-digit IRRs in invested capital. I’ll assume they mean low-double digit and question if this hurdle rate is appropriate.

What Should Be TPL’s Hurdle Rate?

Qualitatively, the hurdle rate for buying outside assets should be higher than repurchasing shares. TPL’s assets are world class and come with more than just royalties. Additionally, management should know assets they own much better than assets they don’t own. For a quantitative view, let’s look at a scenario where they repurchased shares from 2020 to 2023. I assume that shares are repurchased at an average price using the beginning year price and the end of year price. IRRs for repurchases done in these four years range from 25% to 39%. This is the true cost of equity and closer to the hurdle rate that should be used to evaluate outside acquisitions.

Management ultimately executed their first major acquisitions in 2024, deploying $455mm in two do deals in the second half of the year. The cash management held on the balance sheet was a call option on these two deals. However, as seen above, that call option had a hefty premium. I hope that these two deals are successful, but even if they are, will they have been as successful investments as just repurchasing shares? I ran an analysis where I assumed that dividends were capped at the amount deployed into them in 2019, and that the extra cash further went to buybacks. Deploying all excess cash from 2020 through 2023 would have allowed the company to buyback 13.6% of the current shares outstanding. TPL would have deployed $1.2bn into buybacks at an average price of $376.03. Today (10/21/24), those shares are valued at $1,074.57 and worth $3.4bn. By dispensing material buybacks, TPL management destroyed over $2.2bn in value. Is the $455mm they deployed into deals in 2024 worth $2.2bn? Probably not given management’s claims that Permian assets are now well understood. Maybe management got a good deal on these two assets, but they came at a high costs. To be fair, the company did benefit from holding cash on the balance sheet in anticipation of these two deals, and likely more to come. From 2020 to 2023, TPL cumulatively earned $34mm in net interest income attributable to its balance sheet cash. The board made sure that management was well compensated for this. Interest income (but not interest expense) counts towards management’s EBITDA bonus calculations. In 2023, having interest income in the calculation of EBITDA pushed management into a higher bonus category. I would like to know where is the justice for shareholders for management’s and the board’s capital allocation decisions that led to the destruction of $2.2bn in value?

Note: In the high-cash, buyback era, I don’t distinguish if the capital allocation decisions were made by the legacy co-chairs, the current board, or management. From a shareholder’s perspective, we only see the result. Also, I realize that the analysis makes some broad assumptions, such as early purchases not affecting the future prices paid for stock. While I realize that this would likely to occur, the direction of and magnitude of the analysis is correct.

Excerpts for 2/22/24 Earnings Call

Disclaimer: For entertainment purposes only. This is not an offer to buy or sell any security. Due your own due diligence.

How much of the increased IRR from share repurchase was due to multiples expanding? That is not foreseeable / under mgmt control and therefore it probably shouldn't be in a cost of capital calculation... if you re-ran the IRR from repurchase #s but kept the multiple flat, what kind of return would they have earned (from growth in underlying CFs)?

This is so well written and its supported by data and clearly explainable charts. Much better than VIC! Thanks for sharing